Jill Swenson stands outside a bookshop in Appleton, Wis., on Nov. 27, 2021. The Affordable Care Act made coverage accessible to Swenson, but paying for it was still a stretch; premium subsidies have helped. ACA marketplaces have adopted policies that connect consumers to coverage by reducing administrative burdens, helping them navigate their plan options, and taking steps to reduce health and coverage disparities. Photo: Sara Stathas/New York Times via Redux.

More people than ever rely on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces for health insurance. 1 Millions more will become eligible for marketplace coverage after losing Medicaid as the pandemic-related pause on redeterminations comes to an end. 2 Amidst this flurry of enrollment activity, policymakers running the ACA marketplaces shoulder the great responsibility of connecting consumers to affordable coverage that meets their health and financial needs. After years of attempts to overturn the ACA in Congress and at the Supreme Court, the marketplaces, now in a relatively stable political and legal environment, may have an increased opportunity to pursue innovative and consumer-friendly policies.

While most Americans are insured through their employers or public programs, such as Medicare or Medicaid, more than 18 million people depend on the private individual health insurance market for coverage. 3

The ACA transformed this insurance market. Before the ACA, people purchasing insurance on the individual market faced significant barriers to comprehensive and affordable coverage. Insurers competed through discriminatory policies, benefit designs, and pricing schemes, frequently denying insurance applications, creating products designed to cherry-pick healthy individuals, or offering only paltry or unaffordable coverage to people with preexisting conditions. 4 Consumers lacked a neutral, centralized source of information about insurance products, making it difficult to compare plans. 5

The ACA outlawed these discriminatory practices in the individual market and created “marketplaces,” a one-stop shopping experience on a trusted government website to enroll in federally subsidized health insurance plans that meet a common set of coverage standards. Marketplaces were meant to foster competition on price and value, facilitate meaningful plan comparison, and allow consumers to enroll in affordable, comprehensive private coverage. 6

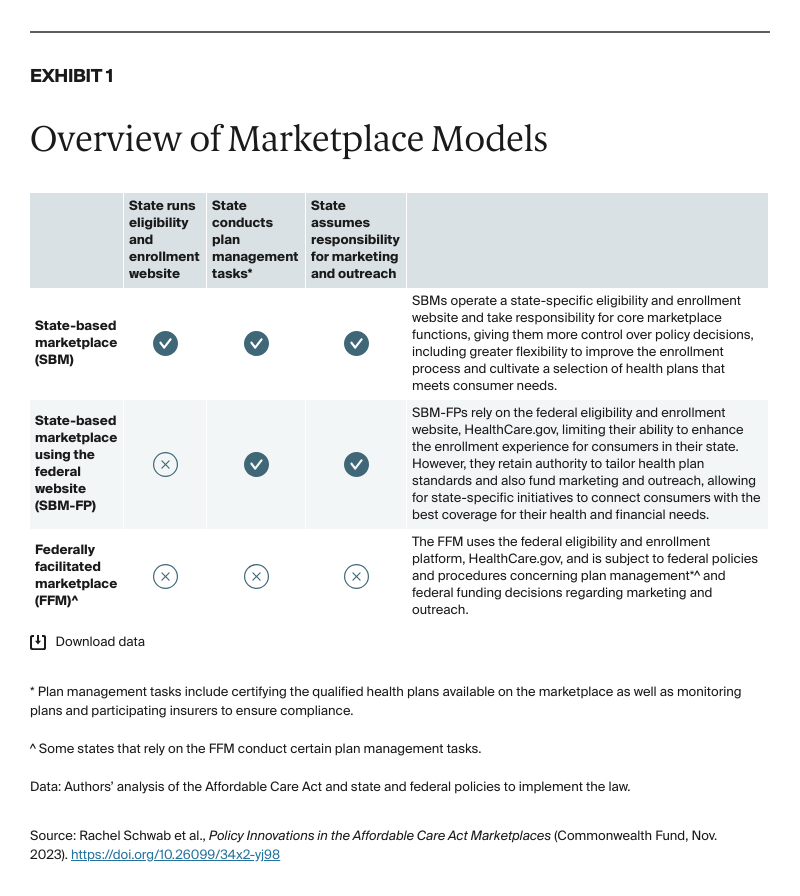

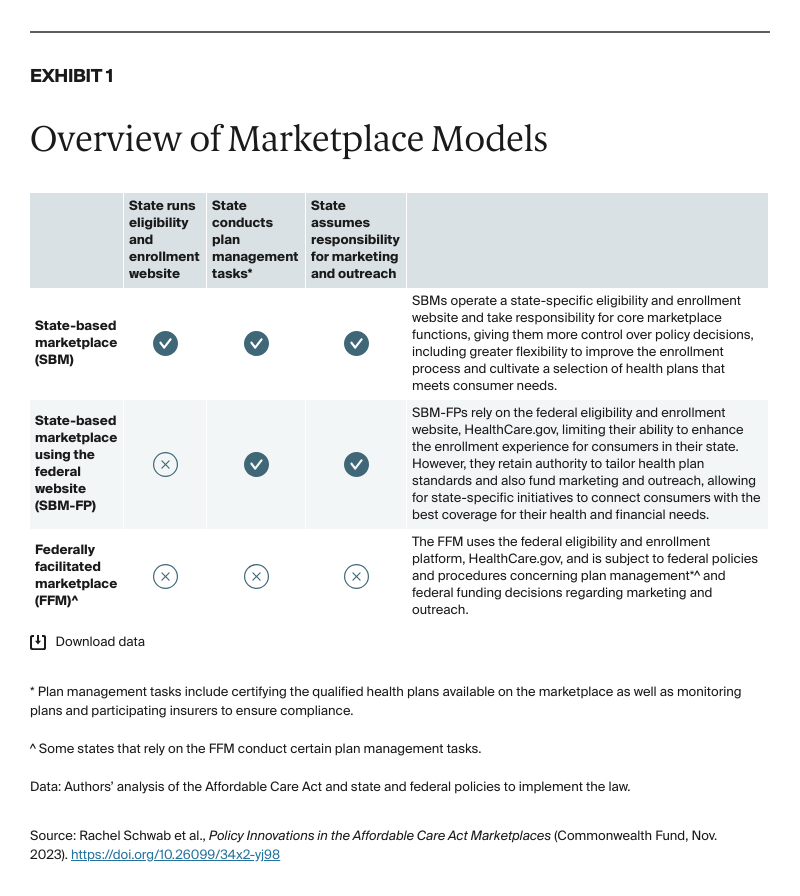

Marketplaces were originally envisioned as a state-operated mechanism. However, in part because of opposition to the ACA, most states initially ceded responsibility for running their marketplace — and with it, the opportunity to use these platforms to drive state innovation — to the federal government. 7 In 2023, 20 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) operate a state-based marketplace using a state-run eligibility and enrollment website (SBM) or a state-based marketplace using the federal eligibility and enrollment website, HealthCare.gov (SBM-FP). The remaining 30 states rely on the federally facilitated marketplace (FFM) (Exhibits 1 and 2).

When the marketplaces launched in 2013, website failures and political opposition to the ACA hindered enrollment efforts. 8 After some progress in the first couple of years, enrollment dipped again between 2017 and 2020 amidst federal policies that undermined the marketplaces, lackluster insurer participation, and significant premium increases. 9 But following congressional action to expand federal premium subsidies, and under the stewardship of a more supportive administration, marketplace enrollment rebounded, with a record 16.4 million people selecting a marketplace plan in 2023 — more than double the enrollment seen in the inaugural sign-up period. 10

The large number of people relying on the marketplaces for health insurance underscores the importance of crafting policies that promote quality and affordable plan options as well as procedures that make it easy to shop for, enroll in, and maintain coverage. This brief identifies key policies adopted by the ACA marketplaces designed to remove known obstacles to accessing the comprehensive, affordable coverage available through the marketplaces and support health and financial well-being, including marketplace efforts to reduce enrollment barriers, simplify plan choice, promote market competition, and increase health equity. We reviewed these policies across the 18 SBMs, the three SBM-FPs, and the FFM for 2023.

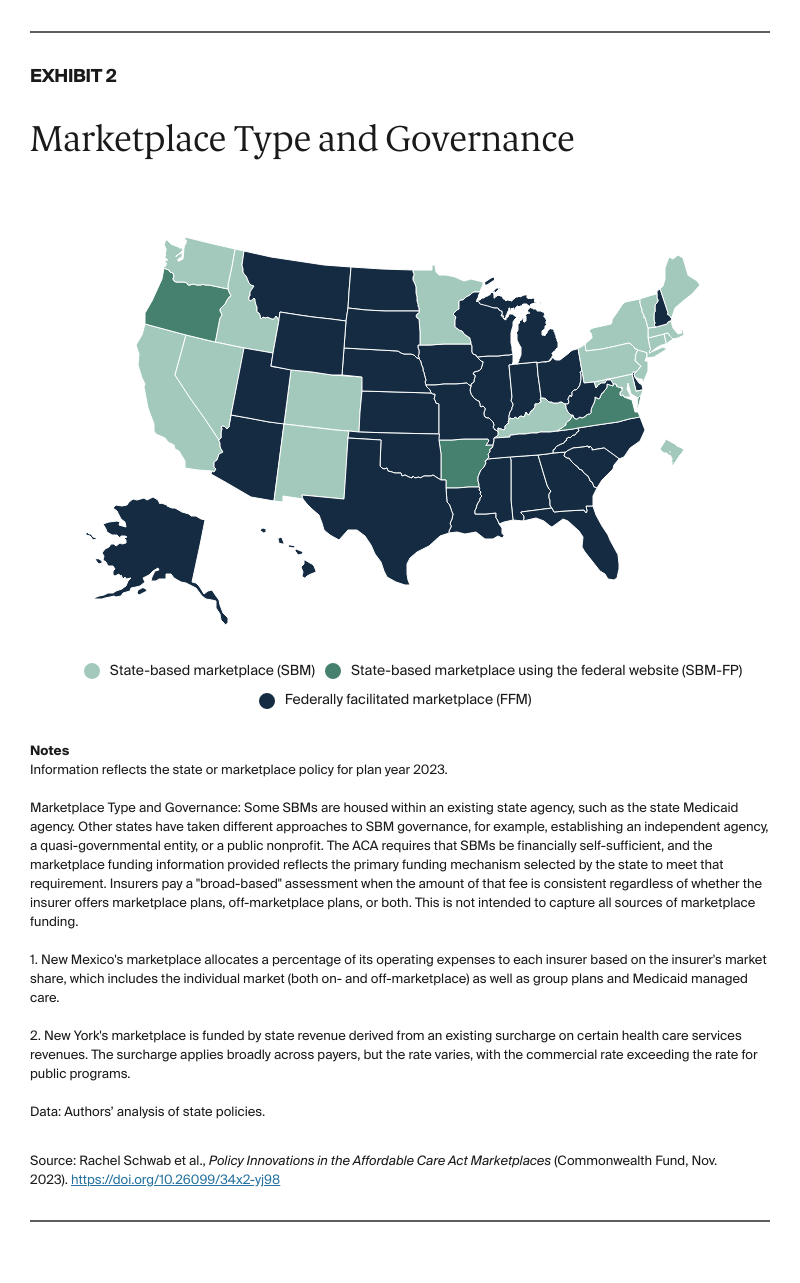

The ACA reduced the uninsured rate to an historic low, but around 8 percent of people still lack coverage, including people who are eligible for subsidized marketplace plans. 11 Some of the eligible but uninsured are deterred by the administrative burden of enrolling in coverage, reducing sign-ups and take-up of available financial assistance. 12 Marketplaces have adopted policies to help alleviate this burden and make it easier to enroll in subsidized health plans (Exhibit 3).

Many marketplaces have implemented policies that aim to remove enrollment obstacles by streamlining and even automating the sign-up process. Five SBMs have used the flexibility afforded by a state-run eligibility and enrollment website to establish “Easy Enrollment” programs that allow residents to indicate on their tax forms if they are uninsured and interested in coverage. 13 The state then uses income information from the return to provide an eligibility determination and direct the consumer to Medicaid or a midyear enrollment window for subsidized marketplace plans. 14 Beyond tax filing Easy Enrollment programs, this simplified sign-up process can also operate through other contact points between states and consumers. Maryland, for example, allows people filing unemployment insurance claims to check a box to receive information about affordable health insurance options, and the marketplace offers an enrollment opportunity if they are eligible for marketplace coverage. 15 Four SBMs have set up auto-enrollment programs, eliminating the need for consumers to actively select a plan and preventing coverage gaps when consumers transition between Medicaid and the marketplace. 16 Some states operating SBMs have subsidized premiums for auto-enrolled individuals, reducing or in some cases removing the burden of paying premiums to effectuate enrollment. 17

The FFM has also adopted policies intended to make enrollment easier. In addition to extending the open enrollment period into January in all 33 states that use HealthCare.gov, federal regulators established a new special enrollment period that allows individuals and families with lower incomes — who disproportionately lack health insurance — to enroll in marketplace plans throughout the year. 18 Sixteen SBMs offer some version of a low-income special enrollment period, including several SBMs that expanded the policy’s reach by setting income eligibility thresholds higher than the federal cutoff of 150 percent of the federal poverty level. 19 Meanwhile, to ease transitions to the marketplace for the millions of individuals being disenrolled from Medicaid during the resumption of eligibility redeterminations, the FFM opened an extended and more flexible special enrollment period until July 2024. 20 All but two SBMs have adopted a new, extended special enrollment period for this population. 21

Although the ACA marketplaces made it easier for consumers to compare options across insurance companies, selecting the right plan remains a challenge. 22 The complexity of comparing premiums, cost-sharing structures, benefit designs, provider networks, and formularies is exacerbated by the dramatic increase in plan options on the marketplaces — the average number of qualified health plans available to consumers shopping on HealthCare.gov more than quadrupled between 2019 and 2023. 23 “Choice overload” and the challenges of comparing complex insurance products can lead consumers to make suboptimal plan selections or even abandon the enrollment process altogether. 24

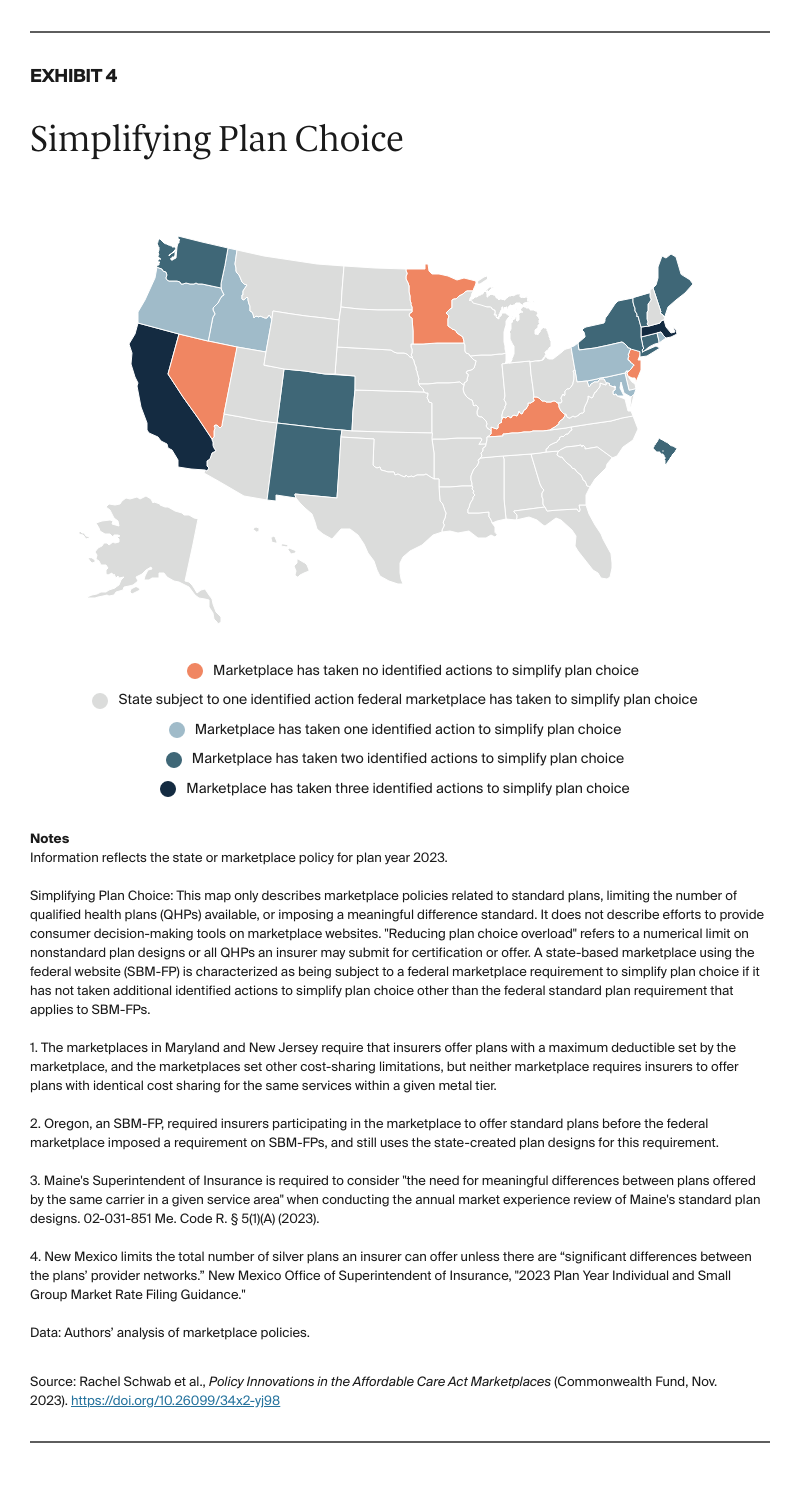

Marketplaces have taken a variety of approaches to simplifying plan choice (Exhibit 4). In plan year 2023, all marketplaces that use HealthCare.gov and nine SBMs required plan standardization, mandating that insurers offer at least some marketplace-designed plans with identical cost-sharing structures (deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance) within a given metal tier. This standardization allows consumers to more easily compare qualified health plans based on characteristics like premiums and provider networks. 25 Standard plans are also a vehicle for marketplaces to reduce or eliminate cost sharing for certain health services, which can improve the value of qualified health plans and lessen health disparities. 26 Seven SBMs also tackled choice overload this year by limiting the number of nonstandard plans or otherwise capping the number of qualified health plans an insurer can propose or offer. Next year, the FFM will limit the number of nonstandard plans insurers can offer on HealthCare.gov. 27 And in 2023, nine SBMs required that an insurer offer additional plans only if they are “meaningfully different” from the insurer’s other products, putting downward pressure on the number of plan options consumers have to compare.

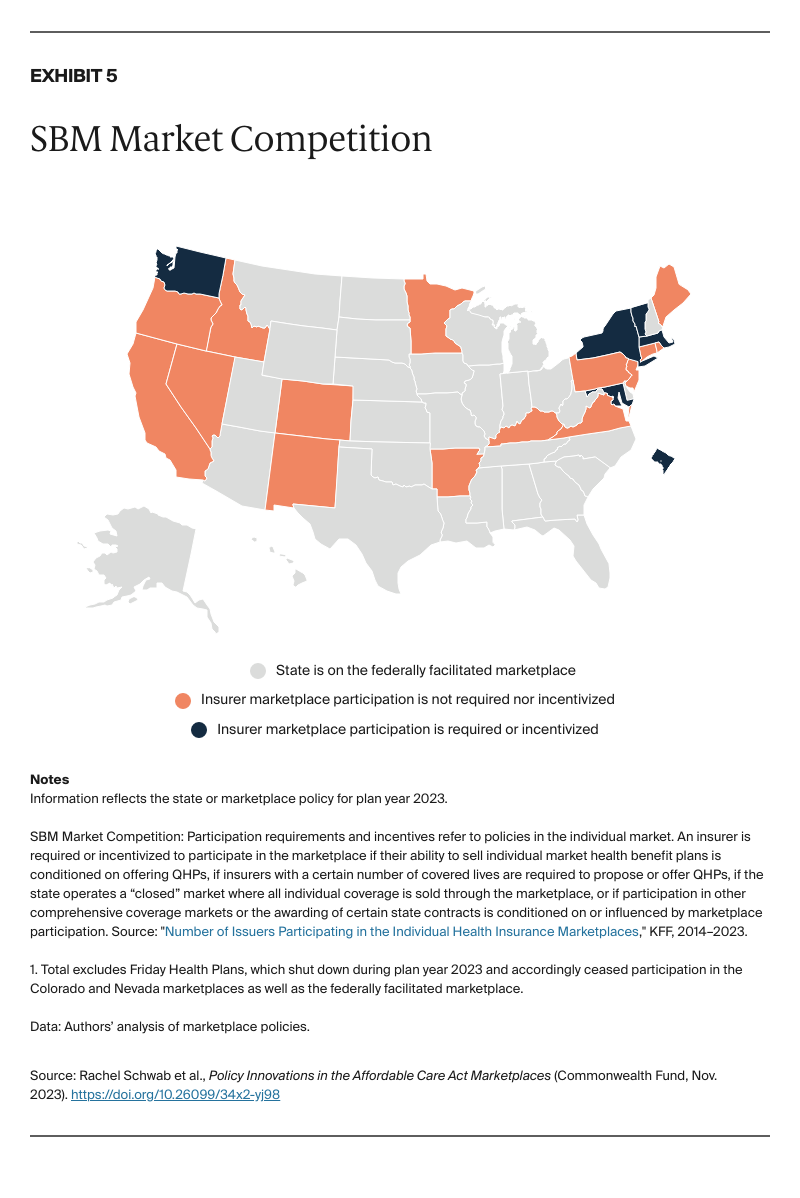

Competition between insurers drives the availability and affordability of plans for consumers who depend on the marketplace for coverage. Greater insurer participation is associated with lower premiums. 28 Participation has fluctuated over the marketplaces’ 10-year lifespan, and insurer exits led to a serious threat of counties with no available marketplace plans in 2018. 29 Six SBMs have implemented policies that require or incentivize insurer participation (Exhibit 5). For example, Massachusetts requires that insurers with more than 5,000 enrollees in the combined individual and small-group market file a response to the plan certification solicitation issued by the marketplace. 30

Some SBMs condition insurers’ eligibility to contract with the state for other lines of business — such as the Basic Health Program (New York) or certain public employee health benefit plans (Washington) — on marketplace participation. 31

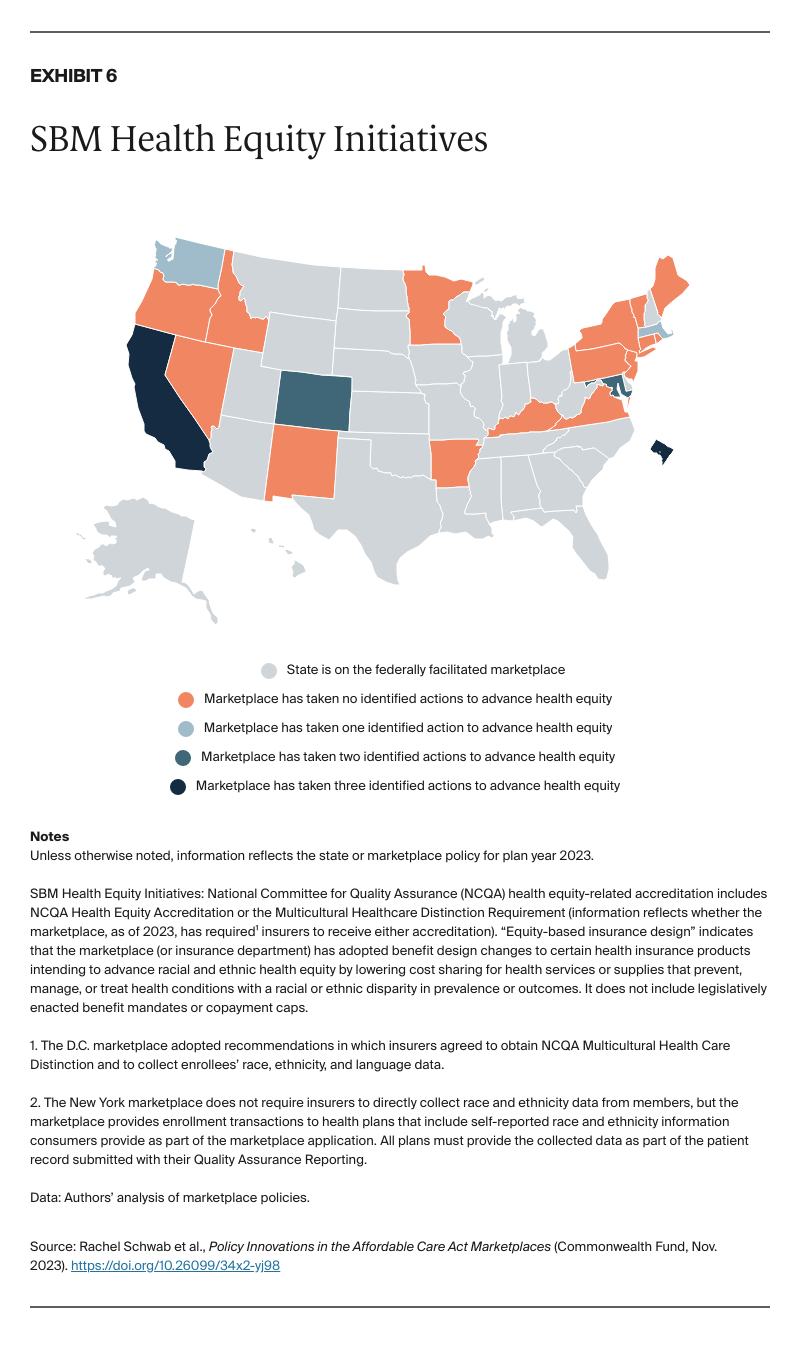

Although the ACA helped reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health coverage and care access, health inequities persist, even among the insured. 32 Marketplaces have adopted policies aimed at improving health equity among enrollees, including through the rules and standards for participating insurers (Exhibit 6). Equity-based insurance design requirements, implemented by five SBMs as of 2023, are intended to increase access to care that prevents and treats conditions with known racial and ethnic disparities, including diabetes, maternal health, asthma, and hypertension. 33 For instance, the D.C. marketplace requires standard plans to include $0 cost sharing for specified medical devices, medications, and health services for patients with diabetes. 34

A small but growing number of SBMs require insurers to obtain health equity–related accreditation from the National Committee for Quality Assurance, which assesses how effectively health insurers advance health equity across several dimensions, including demographic data collection and reporting practices, the provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services, and affirmative steps to reduce health inequities and improve care quality. 35

Finally, four SBMs require insurers to collect and report race and ethnicity data to help quantify and reduce disparities and inequities in insurance coverage, health care access, and health outcomes. 36 In a similar vein, federal regulators will soon require all insurers that participate in the marketplace risk adjustment program to “make a good faith effort” to collect and submit enrollees’ race and ethnicity data. 37

The Affordable Care Act marketplaces are now a fixture in the health insurance landscape. Though enrollment is modest compared to other sources of coverage, marketplaces provide health insurance to some of the most under-resourced communities, including workers without employer coverage, families just over the income cutoff for Medicaid, and people who lose their health plan. Marketplaces also allow people to change jobs, start their own business, or retire by serving as a reliable source of affordable, quality coverage for people without access to job-based insurance. The role of the marketplaces takes on additional importance when access to other sources of coverage is disrupted, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic or the current “unwinding” of continuous Medicaid coverage, when 15.5 million people are expected to lose Medicaid. 38

Today, a record number of people rely on the marketplaces for coverage, and millions of uninsured individuals are eligible for subsidized marketplace plans. 39 Many marketplaces have risen to the occasion, adopting policies that seek to encourage enrollment, help consumers identify the best plan for their health and financial needs, promote insurer participation, and advance health equity. These range from innovative policies, such as Easy Enrollment and auto-enrollment programs; tried and true tools, including plan standardization; and policies that lay the groundwork for future action, like data collection requirements to better understand health and coverage disparities.

Wide variation in marketplace policies across states, however, has created a patchwork of marketplace enrollment procedures and plan standards, likely leading to different enrollment experiences and outcomes for consumers. Both the FFM and SBMs have established innovative policies later adopted by some, but not all marketplaces, including the federal low-income special enrollment period and standard plan requirements. Nationwide adoption of these policies, as well as other proactive efforts to bolster and expand access to this crucial source of coverage, could lead to more consistently consumer-friendly marketplaces in every state.